The Panic of 1907 crippled the financial markets, brought ruin to banks and trust companies, all but bankrupted the Treasury of the United States of America, and required the intervention of J.P. Morgan to end. And it directly led to the founding of the Federal Reserve System in the United States, in 1913. I was researching the crisis this past semester while taking my History of American Economic Development class at the University of Missouri — Saint Louis (I took it with Professor Rogers, and I recommend it highly). I wrote my final paper on the crisis, though I ended up relying on just two primary sources. Immediately after the semester ended I found several others that would have been very useful in my research—I’m planning to go back and revise this to include them, but I haven’t done it yet.

The events leading to the panic began on October 14th, 1907, after a wealthy investor overextended himself while attempting to corner the market in copper.

F. A. Heinze lost more than $50 million dollars in under a day after investors realized what he was attempting, and the United Copper Company’s shares fell from $62/share to less than $15/share. (Federal Reserve Bank of Boston 3) On its own, this would have been disastrous for Heinze and other copper speculators, but would have little effect on other investors. Heinze, however, was the owner of the State Savings Bank of Butte Montana, which became insolvent almost immediately due to its holding large amounts of United Copper Company shares as collateral. Heinze was also president of the Mercantile National Bank—and once depositors learned of his financial peril, they rushed to withdraw their monies from that institution as quickly as was possible. Heinze was forced to resign his position from the Mercantile National Bank on the morning of October 17th, but the damage was done. Depositors began removing money from the Mercantile National Bank to deposit it in other banks in the area.

At this point, the panic had not yet truly begun. The financial markets were still feeling the effects of Heinze’s manipulations, and his banks were collapsing, but the overall system was still sound. And then it was discovered that one of the directors of the Mercantile National Bank, Charles Morse, controlled seven other New York banks and had been heavily involved in the copper speculation. He was removed from those banks, but depositors at those banks had already begun removing their money. (Tallman and Moen 4)

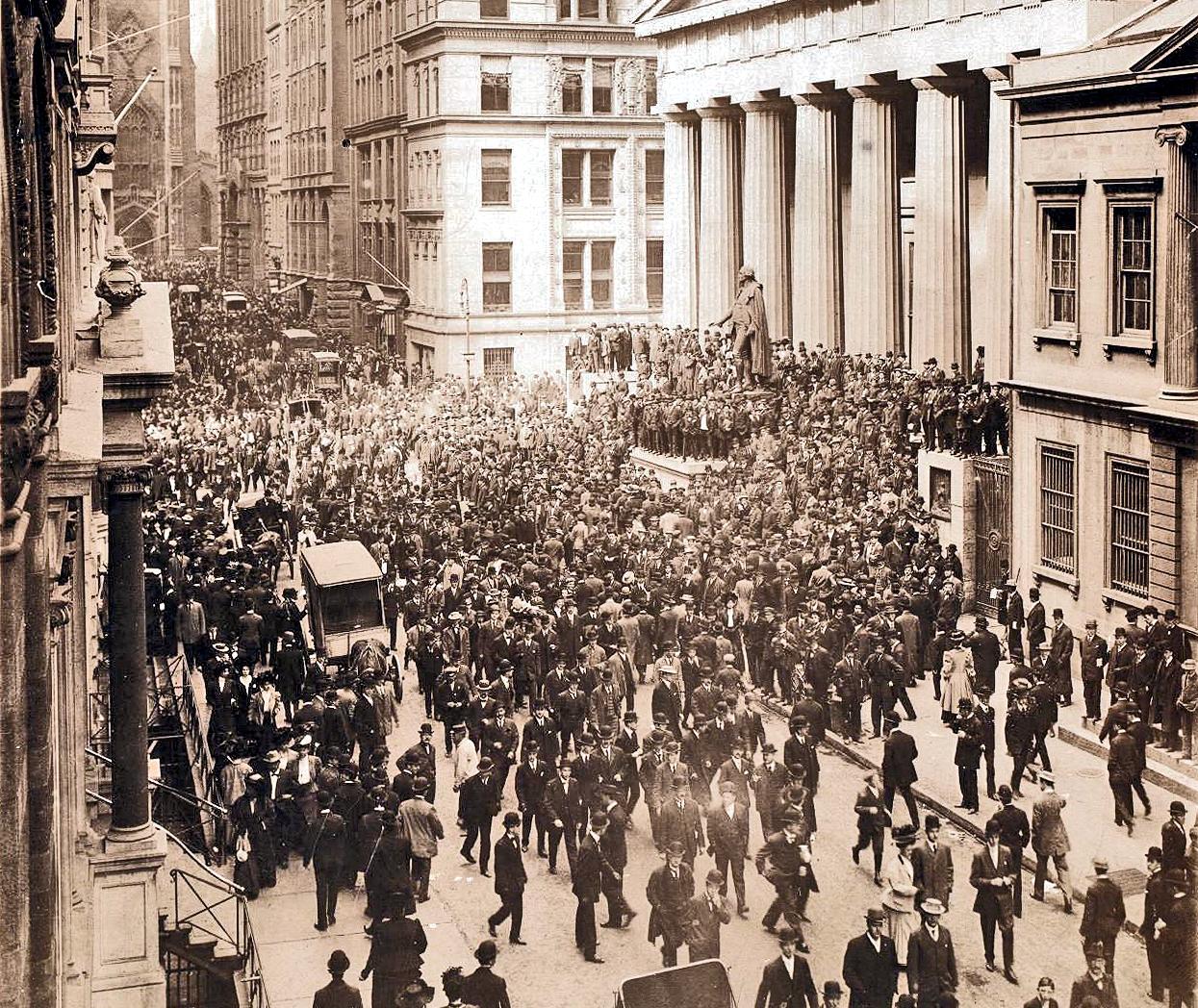

Next to fall was the trusts, starting with Knickerbocker Trust Company, the third-largest trust in New York. J.P. Morgan, widely seen as the last hope for the trust, decided to not provide aid—a decision which led to the trust paying out $8 million to its depositors during a period of three hours on October 22nd, and immediately suspending operations. Another trust, the Trust Company of America, was also hit hard and paid out $47.5 million of their $60 million of total deposits in a period of two weeks. J.P. Morgan, J.D. Rockefeller, and Secretary of the Treasury George Cortelyou deposited a combined $38 million into the trusts and banks to prop them up and allow them to continue operating. (Tallman and Moen 8)

Meanwhile, the stock market was in trouble. Brokers regularly borrow and lend money to buy and sell shares of stock, but by October 24th that borrowable money was in extremely short supply. It was only through Morgan’s convincing the banks to loan $25 million to the stock market that the stock market was able to make it through the day; the next day was even more of a struggle, with banks being more and more unwilling to lend. In fact, banks were extremely unwilling to lend to anyone, whether it be fellow banks or to the general public, leading to a shortage of currency in the economy. To add to the difficulty, the city of New York began running out of funds, and was unable to obtain more. Morgan loaned $30 million to the city, allowing them to continue operations. (Tallman and Moen 10)

The panic eventually ended by mid-November, when Morgan convinced the trust companies and banks to support each other during runs. But the situation showed the necessity of an organization dedicated to ensuring that panics were minimized and dealt with in the best way possible; relying on a single man such as Morgan to organize the response was impractical and foolhardy.

J.P. Morgan died on March 31st, 1913, which ended any chance of his being able to repeat his 1907 actions. In December of that year, Congress voted to approve the Federal Reserve Act, which established the United States Federal Reserve. Despite the intentions of its creators, the Federal Reserve was unable to prevent the Great Depression (though I believe that that’s more because of its reliance on the gold standard, which prevented it from printing money to pay off debts and bail out banks, than of anything else. There’s some evidence for this—when the gold standard was temporarily suspended, the economy immediately began to do better).

Looking back at the 1907 Panic, it’s clear that there were few regulatory oversights. Indeed, there was little government involvement at all—J.P. Morgan basically controlled the entire response, including controlling where the money was being allocated to fight the panic, and how it was handled in the press. The Treasury did place $37.6 million in the banks to help secure them, and supplied an additional $36 million to help alleviate runs on banks, but that expended their total power (after doing that, the Treasury’s working capital had dwindled to $5 million). (Tallman and Moen 8) This would indicate that the market can self-regulate to a degree, at least when getting out of a bad situation, provided there’s someone who is well-versed in how to allocate large sums of money to get things done.

It’s also clear that allowing people who own or manage banks to engage in speculation with bank money, no matter how well-founded and reliable they believe it to be, is foolhardy. If Heinze and Morse had lost their own fortunes, it wouldn’t have caused a panic. It was only when it was discovered that they were using their banks to help finance their personal speculation that the bank runs started, and the panic took off. In addition, allowing one person to outright control three banks and heavily influence four others, as in the case of Charles Morse, does not seem like a particularly good idea for anyone involved. I believe that if that were to happen today people would probably be concerned about conflict of interest and moral hazard (and for very good reason).

All in all, the Panic of 1907 could have been much, much worse. Instead of bank runs, sensational headlines, and a nice story for the economics textbooks illustrating the need for a central bank to keep everything running smoothly, it could have ended in a huge economic downturn that could have heralded in the Great Depression somewhat earlier than it did (or at least a fairly major recession; the Great Depression was a worldwide event, not something that was restricted to the United States). Instead, due largely to J.P. Morgan’s acting as a central banker and lender of last resort, it lasted scarcely a month and served mostly as a warning for the perils of an unregulated financial system.

Works cited:

Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. “Panic of 1907.” n.d. The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. PDF.

Tallman, Ellis and Jon Moen. “Lessons from the Panic of 1907.” Economic Review (1990): 2-13. PDF.

Note about references: While originally researching this paper, I was unable to find many other quality resources regarding the panic (at least, not many that were online). If you can recommend further resources, please contact me and let me know! I would love to revise this piece to include them.